EXPLORE

ISLE OF HOPE’S

GEOGRAPHY

Beginning in 1752, less than twenty years after its first settlement, Isle of Hope landmarks and the island itself began to appear in maps of the day. Some were surveys of large expanses of land, such as maps of the State of Georgia, with Isle of Hope being a minor feature and sometimes merely designated with a dot. Others were lot-level maps of Isle of Hope land with great detail about specific properties. Between these extremes were maps that depicted the entire island or its major portions.

Each map reveals important information, including property owners and property lines, locations of roads, railroads, and ferries, as well as topography and growth patterns. The selection below includes some of the best examples of Isle of Hope maps. Several of the maps are never-before-seen compilations of other maps. Others are magnified detail of the Isle of Hope portions of much larger maps.

Sixteen years after the founding of Isle of Hope, cartographer William DeBrahm identified the settlements of “Cap: Jones” and “Henry Parker Esq: President” on his topographic map of the coast of Georgia. He did not identify Isle of Hope itself, only these two individual settlements. This was the first time any landmark on Isle of Hope had been identified on a map. This map is a magnified view of the small portion of DeBrahm’s map that relates to Isle of Hope. DeBrahm’s entire map, entitled, “A Map of Savannah River Beginning at Stone-Bluff, or Nexttobethel, which Continueth to the Sea, also the Four Sounds Savannah, Hossabaw, and St. Katherines and their Islands”, depicts hundreds of miles, first along the Atlantic Ocean and then up the Savannah River border with South Carolina. This is one of DeBrahm’s earliest maps in colonial America. He would later become Surveyor General of Georgia and South Carolina and is considered one of the great mapmakers of the eighteenth century. The detail relating to Wormsloe includes Noble Jones’ four bastion fort and his “garde haus” protecting the river route south of Savannah. Henry’s Parker’s home is also shown on northern Isle of Hope. The straight-line, clear-cut vistas between the two settlements, which were used for trails and signaling, are also shown. Color-coding identifies the island’s bluffs, marshes, pine barrens, and oak lands. (Special Thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

This is detail from the earliest map that identifies Isle of Hope. The larger map, by renowned cartographer Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres (1722-1824), shows the Atlantic Coast from St. Catherine’s Island in the south to the May River in the north. DesBarres created The Atlantic Neptune, a four-volume atlas that is considered the most important collection of maps of North America in the eighteenth century. The detail relating to Isle of Hope shows three different settlements along an unlabelled waterway that is the Skidaway River. These three settlements correspond with the three original settlement on Isle of Hope dating back to 1736, forty-four years before the map was created. The first settlement shown in the south of Isle of Hope corresponds to the land grant for the Jones property at Wormsloe. The second settlement in the middle corresponds to the original property of John Fallowfield, who left the colony in 1742. His property was forfeited and later also given as a land grant to the Jones family. The third settlement corresponds to the original property settled by Henry Parker and given in a land grant to his wife Ann after his death. (Special Thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

This beautiful, hand-colored map shows Isle of Hope at the time of the Revolutionary War. In 1778, the British under Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell invaded Georgia and captured Savannah and Augusta. In 1780, Campbell created a much larger, uncolored map based upon his military campaign along the Georgia coast and up the Savannah River. His complete map provides information about the siege of Savannah as well as other towns, plantations, and roads in colonial Georgia his troops encountered during the British invasion. Isle of Hope played no role in Campbell’s Revolutionary War military operations. The part of Campbell’s map relating to Isle of Hope contains far less detail than other areas of his map where his troops were active. Isle of Hope is depicted as a heavily wooded, sparsely populated island. There are only two settlements shown on the island, one for Jones and one for Parker, two of the families who first settled Isle of Hope in 1736. Both settlements are depicted as cleared land surrounded by wilderness. The Jones settlement, which depicts Wormsloe plantation, shows a single structure. The Parker settlement farther north upriver shows four structures. Parker’s settlement is labelled “Parker’s Ferry,” indicating that there was a ferry to Skidaway Island from the north end of Isle of Hope. Across the river on “Skedway Island” was a road leading to the interior of the island. This ferry was short-lived. Later maps of Isle of Hope do not show a ferry on the north end of the island, instead showing a ferry to Skidaway Island on the southern end of Isle of Hope near Long Island. The few roads depicted on Campbell’s map are straight lines. One is a road from the mainland to Parker’s Ferry along what would now be near Skidaway and Parkersburg Roads. The other two roads are clear-cut paths between Parker’s Ferry and the Jones’ settlement and between Jones’ settlement and the “Orphan House” at Bethesda. Those two clear-cut trails, straight as arrows, served not only as roads but also as signaling systems between the settlements. Outside of these two settlements, Isle of Hope is depicted as untouched forest and completely uninhabited. This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

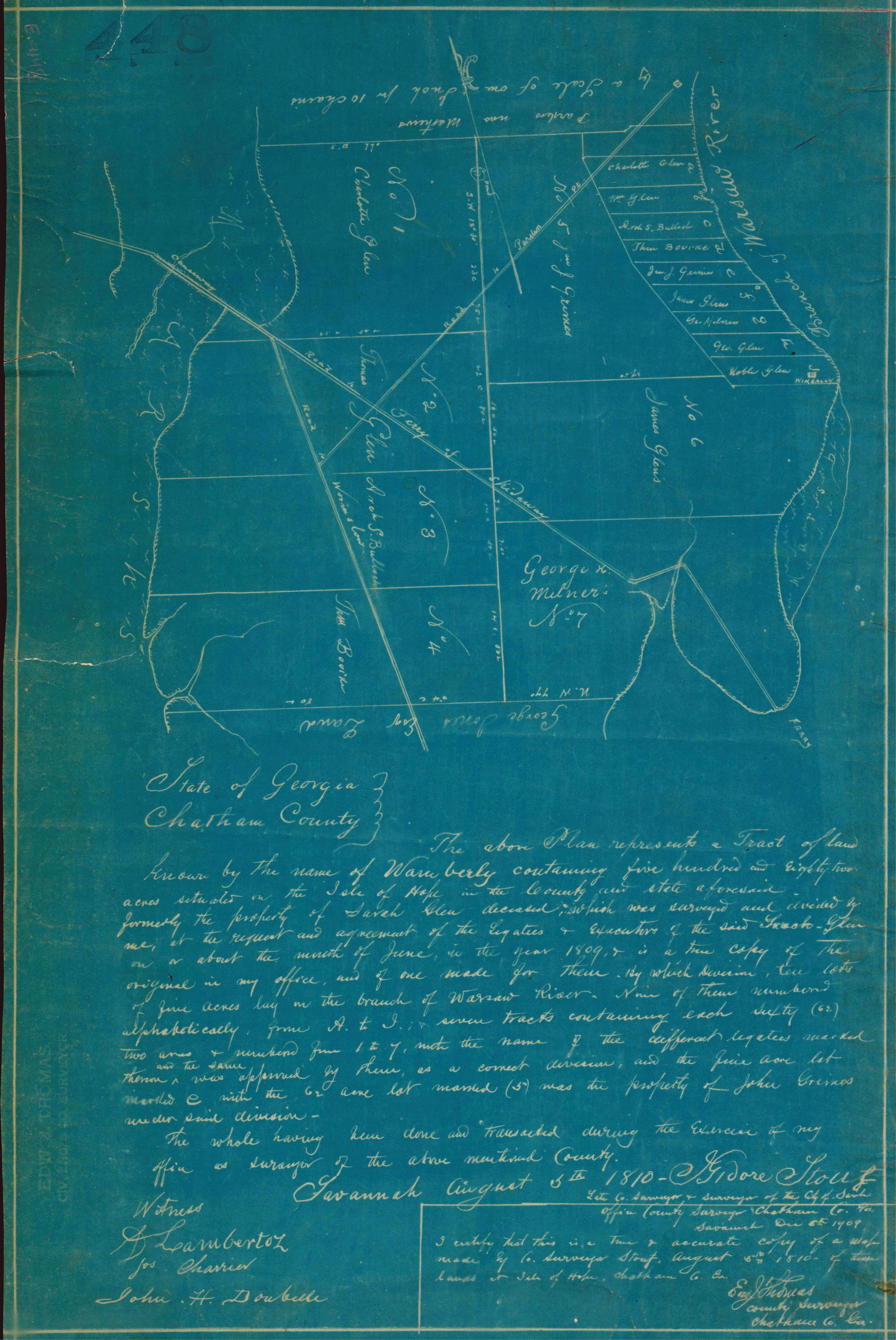

This checkerboard map by Isidore Stouf shows the first subdivision of Wymberley and the beginnings of the Bluff Drive properties as we know them today. From 1736 until 1810, the first three generations after Isle of Hope was settled, the 500 acres of the Wimberly Plantation was a single, undivided piece of property. In 1810, when this map was created, Wimberley Plantation was owned by one woman, Mrs. Sarah Jones Glen, the granddaughter of one of Isle of Hope’s original settlers, Noble Jones. Noble Jones received the land directly from King George. Noble left the land to his son, Noble Wimberly Jones. Noble Wimberly Jones gave the 500 acres intact to his daughter Sarah. Sarah had a plantation house, kitchen, and gardens at Wimberly Plantation when she died in 1804. She was a widow, having outlived her husband, John Glen, who had been Savannah’s mayor and the first Justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia. Sarah and John had thirteen children. Ten were living when Sarah died. This map was needed because Sarah’s will did not provide details on how the entire 500 acres should be allocated among her many children. She only specified the recipients of two five-acre lots. She gave her the five-acre riverfront lot with her plantation house to her oldest daughter, Margaret Glen Hunter. Margaret received special treatment because she also was a widow, as her husband had been recently killed in a duel. Sarah Glen also set aside a second five-acre river lot for son Noble Glen. How to divvy up the remaining 490 acres turned into something of an ordeal. After five years, Sarah’s sons and daughters finally reached an agreement that the property should be re-surveyed and then subdivided into a one group of 5-acre riverfront lots and another group of larger interior lots. The siblings would draw lots and select their lots in order. This map shows the re-survey of the land just prior to the drawing and lot selection. The re-survey revealed that Wimberly Plantation included 582 acres, 82 acres more than previously known. The map shows the selected lots with their owners’ names. The names of Thomas Bourke, John Grimes, George Milner, and A.S. Bulloch are the names of the husbands of Sarah’s daughters. This subdivision of Wimberly Plantation in 1810 would be the largest subdivision of the land until James Richmond developed the Wymberley subdivision in the 1950s. There are several important Isle of Hope landmarks shown on the map. The Skidaway Road of present day is identified as “Road to Ferry of Skidaway” and ends at a point on southern Isle of Hope known as Ferryman’s Point. Parkersburg Road is identified as the “Road to Parker Pt.” The Skidaway River is shown as the “Warsaw River.” The five-acre riverfront lots, known as the “Wymberley Lots”, show the beginning of the modern property boundaries along Bluff Drive. Interestingly, the Glen family plantation house is shown on the map and identified as “Wimbally”, However, the land called “Wamberly” on the text in the map’s legend. Over a hundred years later, James Richmond would name the area “Wymberley.” That is certainly better than “Wamberly”.

This map is based on a tracing of the resurvey map by John McKinnon as described in its transcribed map legend. The colored boundary lines noted in the legend have been added from the original map. As the legend states, the map documents the two-part subdivision of the Parker tract comprising the north end of the island, circa 1800, but also includes the property boundaries of William Parker’s heirs, not mentioned in the legend. This copy also includes later boundary lines of the Thomas Henderson property (in red) and other details not on the original map. (Special Thanks to Karl Schuler) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

This map is an 1881 tracing of an 1846 map which showed the division of Dr. William Parker’s large land holdings on northern Isle of Hope. Dr. Parker was the grandson of Henry and Ann Parker, the original settlers of the northern 500 acres of Isle of Hope. William Parker died a childless widower in 1838 and left portions of his property to his nieces and nephews, Alexander and James Maxwell, William Parker Bowen, Mary Amelia and Ann Mathews White, and Robert Guerard, many of whom are identified on this map. William Parker also willed 10 acres of land on the Bluff to Christ Church, which are shown on the map and labeled the “Church Lots”. Not surprisingly, present day Parkersburg Road is labelled on the map as “Road to Dr. Parker’s”. The map shows far more of Isle of Hope than Dr. Parker ever owned, particularly in the Wymberley area. The “Wymberley Lots”, the group of the five-acre lots along the Bluff which were divided under the will of Sarah Jones Glen, are labeled. “Wormslow Road” and the road from “Skidaway to Savannah” are shown in southern Isle of Hope. Owners of the properties throughout the island are identified and the map gives an important roster of Isle of Hope landowners at the time. The original 1846 map was traced in 1881 in connection with a land purchase by Charles Henry Seton Hardee that year. The maps includes great detail about the area around on northern Isle of Hope around “Lot 4”, the property being purchased by Hardee. That property became known as “Whitehall’. At that time, Bluff Drive was 70 feet wide and extended all the way to the north end of the Bluff in front of the houses. That portion of Bluff Drive has been blocked off for many years now. (Special Thanks to the Hardee Family)

This map gives a glimpse of Isle of Hope just after the Civil War. Savannah mapmaker Charles Platen worked several years to create a topographical map of all of Chatham County, relying on 37 original deeds, maps, and surveys of portions of the county. He then spent seven months in Philadelphia with a printmaker ensuring that the produced lithographic maps, some nearly 4 feet by 6 feet in size, were perfectly printed. In December of 1876, The Savannah Morning News proclaimed Platen’s work “the handsomest lithographic map in America” and stated, “As a work of art, it is a magnificent specimen, and as an accurate and complete map of the county, its equal has never been seen, and its value cannot be overestimated.” Platen’s map is the first map to show a railroad to Isle of Hope. The Savannah, Skidaway & Seaboard Railroad had reached the island in July of 1869, six years before. Strangely, on Platen’s map, the name of the railroad is printed in mirror-writing and “Skidaway” is misspelled “Scidaway.” The topography of the Isle of Hope is shown with lowlands and swamps colored in green and separated by dotted lines from higher ground colored in yellow. Property lines are shown with the nine “Wymberly Lots” and four “Church Lots” along Bluff Drive blocked off in black. Many of these riverfront lots are intact today. Fort Wimberly and the Jones family mansion are identified in Wormsloe. Skidaway Road is shown leading from the causeway to a bridge connecting Isle of Hope to Long Island, long gone today. LaRoche Avenue, not to be built for a quarter century, is nowhere to be seen. (Special Thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

This map is condensed from the topographic survey map of Chatham County completed by county engineer, Richard Blandford. It documents in detail topographic features such as dams, canals and earthworks, including vestiges of Civil War earthworks. Details also include locations of roads, buildings, cemeteries and other features that in some cases are otherwise undocumented on maps. Numbered coordinates on the 1000-foot grid mark distances south, east and west from the old City Exchange, the current location of City Hall. (Special Thanks to Karl Schuler) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

In 1901, the Savannah Morning News commissioned civil engineer Percy Sugden to prepare a map of Chatham County. The purpose of the map was to spotlight the many advantages Chatham County presented to prospective business owners, such as its large port and waterways, its extensive railroad system and terminals, and its many roadways and streetcar circuits. The entire Chatham County map was published with an accompanying article in a two page spread in the April 4,1901 edition of the Savannah Morning News. The map above is a portion of that larger Chatham County map and focuses on Isle of Hope’s connections to downtown Savannah. Two streetcar lines are shown running from Savannah to Isle of Hope. The Savannah, Thunderbolt, and Isle of Hope Electrical Railway and The City and Suburban Electrical Railway each ran separate rail lines from midtown Savannah out to the Sandfly streetcar station. Once at Sandfly, a single rail line ran from the Sandfly streetcar station across the marsh and to the depot near the bluff at Isle of Hope. Major roads are shown, some labelled and some not. The Skidaway Shell Road and the new LaRoche Avenue, Isle of Hope’s two connectors to Savannah, are identified. Parkersburg Road and Bluff Drive on Isle of Hope are shown with the locations of houses, but these roads are not identified. Grimball Point and Grimball Creek are specifically identified. Grimball Point Road, shown but not identified, leads from the center of Isle of Hope out to Grimball Creek, where five houses are shown grouped on the shoreline of the creek. (Special thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

In 1897, Walter LaRoche proposed the idea of a new, shorter road only to Isle of Hope. The LaRoche family had lived on Isle of Hope since the 1860s when Walter’s father Isaac bought a 50-acre tract of land. LaRoche’s solution not only slimmed down the size of the original beltline idea, but it also reduced its cost through a clever engineering plan. LaRoche’s plan had the new road branch off the county’s existing interior roads and follow the curvature of the coast along the Herb River until it reached the north side of Isle of Hope. There it would connect with an abandoned military causeway temporarily used by soldiers during the Civil War. At the end of the causeway, a new section of road would be constructed to reach the north end of Bluff Drive at the Wylly Place. From there, the existing roads off the island would complete a circuit back to Savannah. Under LaRoche’s plan, Chatham County would finally have its coastal beltline road and it would not have to build a costly new causeway over the marshes on the northside of Isle of Hope. To pressure Chatham County to build the road, LaRoche drew up a petition and circulated it to Isle of Hopers and other southsiders. 600 signed it. Chatham County agreed to build the road and even named it, “LaRoche Avenue.” Construction began in 1900 and was completed two years later. Originally intended to be a clay road, the county later decided to “harden” the road and pave it with gravel and chert. With the opening of LaRoche Avenue, the drive to Isle of Hope and back was praised as “one of the prettiest and most pleasant in the country.” Buggy and wagon traffic to the island increased and so did the number of automobiles. Dozens of automobiles visited Isle of Hope each Sunday after the completion of LaRoche Avenue and the paving of Bluff Drive in 1902. (Special thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.

In 1908, the Savannah Automobile Club, with several Isle of Hope representatives on its Executive Committee, hosted the annual championship races of the Automobile Club of America. The Grand Prize race, whose course is shown by this map, was truly an international competition with German, French, Italian and American entries among the twenty teams. One of the reasons Savannah was selected as the race site was its splendid roads and beautiful scenery, especially along the circuit of roads in its waterfront suburbs, including Isle of Hope. These roads formed the 25-mile course that the racers would lap sixteen times with a winning average speed of 65 mph. The course included straightaways where speeds reached 100 mph. However, the stretch at Isle of Hope, from Skidaway Road to Parkersburg Road to Bluff Drive to LaRoache Avenue, had several sharp turns that greatly reduced the speed to 37 mph. One race car of team Italia ran off the course at Isle of Hope and did not finish. (Special Thanks to Dr. John Duncan)

Civil engineer W.O.D. Rockwell’s map provides a detailed plan of the Wormsloe plantation and surrounding areas at the outset of the twentieth century. Landmarks at Wormsloe depicted include the long entrance avenue, the old colonial fort “Fort Wymberly,” and the confederate battery “Battery Wymberly,” as well as hammocks, pine woods, open fields and dams. The location of the Jones family mansion and outbuildings are shown as dots at the end of a road and marked, “Wormsloe.” Shown outside the boundaries of the plantation are Long Island in its entirety and just a bit of Skidaway Island with two bridges, the “long bridge” and the “short bridge,” connecting Isle of Hope to Skidaway Island via Long Island. Portions of undeveloped, pre-James Richmond Wymberly are shown. Present day Parkersburg Road is labelled “To Parkersville.” Also shown outside of Wormsloe boundaries is the route of the Savannah Electric Railway electric streetcar line, “The People’s Electric Railway,” across the island to Isle of Hope’s river bluff. The Savannah Electric Power Company had assumed charge of the streetcar to Isle of Hope in 1902, six years prior.

Illustrated in 1930 by Charleston cartographer Augustine Thomas Smythe Stoney, this map provides a pictorial annotated guide to two scenic drives from Savannah’s urban center to Wormsloe Plantation on Isle of Hope. The early 20th century was marked by the rise in popularity and affordability of the automobile, which created opportunities for many Savannahians to explore beyond their immediate surroundings. Coupled with the expansion of the Good Roads Movement, a new swath of paved concrete roads in Savannah enabled city dwellers and tourists to enjoy a pleasurable drive out to the newly opened Wormsloe Gardens. Stoney’s whimsical map, entitled “How to Get to Wormsloe Near Savannah, Ga.”, was the perfect road map to encourage this adventure. Minding Stoney’s written instructions to “Follow the ARROWS”, the map provides two illustrated routes to navigate from City Hall in bustling downtown Savannah to Wormsloe in the lush azalea and live oak-filled riverside landscape nine miles away. Opting for the coastal route, one would travel south out of the city before turning east onto Victory Drive, where one might glimpse swimmers enjoying an afternoon at Daffin Park lake. Turning south at the “Concrete Cross Roads” onto Skidaway Road and then a slight shift southeast onto LaRoche Avenue, one would enjoy an enchanting view of the river marshes before turning onto Norwood Avenue for a short drive leading to the Isle of Hope causeway and Wormsloe’s grand arched entranceway. The alternative interior route offered a different, more rural experience. Travelling south on Bull Street and then White Bluff Road, one would pass nearly five miles of trees, fields and an occasional church or house. Upon reaching Montgomery Cross Road, where a filling station, store, and working farmland could be found, one would turn east for the last leg of the journey eventually reaching Skidaway Road leading to the final destination, Wormsloe. Both road adventures would have provided a visual and mental escape from the city, allowing one to take in the sights and smells of the natural landscape captured by the artist’s whimsical roadside vingettes. A. T. S. Stoney (1894-1949) was an accomplished illustrator, cartographer, surveyor, civil engineer and army officer. He was the son of Samuel Gaillard Stoney, a Charleston businessman and plantation owner, and Louisa Cheves Smythe. He served in the U.S Army in Europe during World War I and returned to military service in 1942 for World War II serving in North Africa. Between his periods of military service, Stoney used his draftsman skills to produce numerous architectural drawings, pictorial maps, and surveys, which included locations scattered throughout South Carolina and Georgia.

This 1916 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map provides amazing detail of Isle of Hope’s Bluff area from just over a hundred years ago. Beginning in 1867, Sanborn created maps for thousands of cities across the country to assist with property insurance. The maps included not only typical map features, such as streets and property boundaries, but also included the size, shape, and site of all structures, both residential and commercial. Sanborn had created earlier maps for Savannah in 1884, 1888, and 1898. The 1916 Savannah map was the first Sanborn map to include Isle of Hope. This map focuses on the area in the center of the island along the Skidaway River, which at that time was dominated by the businesses and buildings of Alexander Barbee, the Terrapin King. Barbee had been operating at Isle of Hope now for over twenty years with a series of partners, first with George Willett, then with J.H. Bandy, and finally with his son, Willie. The business had grown from a restaurant in the train depot to the sprawling operations shown on this map. A new and improved pavilion and restaurant dominated the waterfront and included a bathhouse, a boathouse, and a pool. (This two-dimensional map does not show the diving tower, popular with island children.) Across the street was Barbee’s Diamond-Back Terrapin Farm with tin-covered sheds housing eighteen terrapin crawls for thousands of turtles. Nearby was an ostrich pen, home to Marguerite the ostrich and her ostrich friends, an aviary with a pool for birds, and a zoo, which at various times had a sloth, a tiger, a monkey, an anteater, wildcats, and assorted snakes. The map shows our Lady of Good Hope Chapel and the Isle of Hope Methodist Church. An African American church is identified on Parkersburg Road, near the current site of the Isle of Hope School. The school identified in the map is across Parkersburg Road. There is no St. Thomas Episcopal Church, which explains why there is not yet a St. Thomas Episcopal Avenue. Many other streets look familiar and have familiar names, but some have been renamed over the years. Bluff Drive is named River Road and Rosenbrook Avenue is Depot Lane. Many Bluff residences shown on the map are still standing, including Liberty Hall at 25 Bluff Drive, (marked by no. 223), the cottages at 27, 29, 31, and 33 Bluff Drive, (nos. 229-232), and 35 Bluff Drive (no. 233).

This map shows James Richmond’s vision for his subdivision “Wymberley” and was included as a centerfold in the sales brochure for the development. The layout of the subdivision as built differs slightly from this early map. Note that only three streets are named at the is time, Noble Glen Drive, Avenue of Pines, and Richmond Drive. Richmond would later name the other streets after the prior owners of the Wymberley land (Col. Estill Avenue and Flinn Drive), his wife (Dorothy Drive), and his daughters (Nancy Place and Diana Drive). A few notable homes are illustrated along with a few jumping fish and some seagulls.

This wartime photograph, labeled “SECRET”, provides a spy plane’s view of Isle of Hope. While there is no residential development in Wymberley or Paxton Heights in 1942, there is cleared land on north Isle of Hope that is the start of a new subdivision. Isle of Hope’s Skidaway River waterfront is lined with docks and looks very active. It does not appear to be a “No Wake Zone” in the 1940s. Barbee’s operations are clearly visible with the diving tower reaching skyward. The Skidaway Road and LaRoche Avenue causeways can be seen cutting through the surrounding marsh as well as the streetcar causeway reaching from Central Avenue towards Norwood. Roads and clearings on Wormsloe among its densely wooded forests. The rest of Isle of Hope is also densely wooded. Away from the Bluff, the greatest areas of clearing are on northern Isle of Hope. That will change in the coming years. (Special Thanks to Forrest Willoughby) This map is owned by IOHHA and protected by U.S.and international copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution without the written permission of IOHHA is prohibited and illegal. © Isle of Hope Historical Association 2026.